Did You Bet on the Preakness?

Triple Crown season always reminds me of Seven Days in May, the political thriller by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II. Well, I should confess, it has always reminded me of the *movie* Seven Days in May. Because—shame on me—I had never actually read the book. Last week I decided it was time to finally give it a try.

Unfortunately, there is no way to talk about the book without giving away the central premise, but since the hero figures it out by the end of chapter two, it’s not much of a spoiler: Seven Days in May is about a military coup against the President by members of the American military. It’s set in an imaginary near future (a decade after the publication date), so technically that also makes it science fiction (or if you prefer, speculative fiction).

Alternate History

Seven Days in May is definitely a period piece. What makes it so fascinating is which period that happens to be. I was happily reading away when I stumbled over a casual reference to Mrs. Kennedy redecorating a room in the White House. Something about it made me pause and check the book’s publication date—1962. That gave me chills. John F. Kennedy was alive when this book was written. The future stretched out in front of him, in front of the whole country, limitless and unmarred, full of possibilities that those of us living in the aftermath of his assassination can’t even imagine.

Reading Seven Days in May is part time travel, part journey to a parallel universe. It gives a fascinating glimpse of old Washington. This is a very small world where even senators drive themselves around and answer their own phones. Wealthy lobbyists host cookouts in their back yards attended by women in spike heels, and men drinking gin and tonics. Everybody smokes. Fast women drink martinis and tempt married men to stray, but only in New York City.

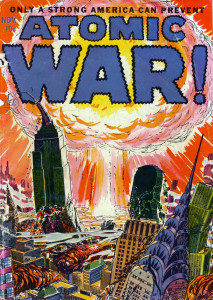

We may not have learned to love the bomb, but we’ve sure stopped worrying.

However, the real sense of dislocation comes from the constant presence throughout the story of the threat of nuclear war with Russia. The coup is precipitated by a disarmament treaty that the conspirators fear will leave America at Russia’s mercy. Although today the hands of the Doomsday Clock are much closer to midnight than they were when this book was written, we have lost the sense of imminent danger that the novel portrays. To really understand the characters and their actions, we need to appreciate that in the world of the story, what is at stake is not just the existence of the United States as a constitutional democracy, but the very fate of the human race.

Rated PG

Another sign of the times is the dearth of violence in the story. The stakes are as high as could possibly be imagined, and the villains are threatening to overthrow the rule of law through military force, but there is no overt threat to the President’s life, or anyone else’s. The only guns in evidence are sentry rifles (never fired), and interpersonal violence is limited to a few fisticuffs. A modern thriller would doubtless have a corpse in the first chapter, and the main character would be fleeing for his or her life before the story was halfway through. In Seven Days in May there’s a lot of sneaking around in the dark and fast driving, but no sense that anyone is in actual danger. When something bad does happen to someone (that’s a tease, not a spoiler), it comes as a real shock.

A Good Read

Aside from nostalgia, is this book worth reading? Definitely. It’s well plotted (though not as exciting as the movie—which is not the criticism it might seem: the movie was scripted by Rod Serling!) and the characters are nuanced, particularly the “good guys” (most of whom are guys—the portrayal of women is very much of its time1), and the main villain is acting (mostly) in what he believes to be the best interests of the country.

One of the story’s major themes is the role of the military in American society, and the other is duty. What does it mean to be a good soldier, and what do you do when you have to choose between following orders and doing what is right? What does it mean to do one’s duty—as a government official, as a member of the military, as a citizen? “Democracy” and “the Constitution” are fine ideals, but if it came down to it, what would you be willing to risk for your country?

Bottom line: Seven Days in May  (3.5 / 5) And be sure to see the movie.

(3.5 / 5) And be sure to see the movie.

So, what does any of that have to do with the Preakness?

[Yes, this is a spoiler, but not a major one.] Operation Preakness is the code name used by the conspirators, who send messages to place a bet on the race as the signal that they are ready to strike. When one military commander refuses to make the measly ten dollar bet, the hero realizes something strange is going on. So betting—or rather, refusing to bet—on the Preakness is the key to uncovering the conspiracy.

______________________________________________________________